The Case Against Interstellar Travel

The speed of light, c, is 299,972,458 m/s, or ~300,000km/s.

So c ? 0.3 * 10^6 km/s.

At minimum, Pluto is 4284.7 * 10^6 km from Earth, and at maximum it is 7528.0 * 10^6 km from Earth. [1]

So at it’s minimum distance from Earth, it would take 4284.7/0.3 = 14282.3 s = 238.0 min ? 4 hr to reach at the speed of light.

At it’s maximum distance, it would take 7528.0/0.3 = 25093.3 s = 418.2 min ? 7 hr to reach at the speed of light.

That’s not terrible.

But the best we’ve achieved in terms of spacecraft speeds is probably the Helios probes, which reached a speed of about 70.22km/s which is a mere 0.000234c, or a paltry 0.0234% of the speed of light. Note that this was an unmanned craft, was not meant to escape our solar system, and was achieved with the help of the Sun’s gravity. What’s impressive is that this was accomplished back in the mid 1970’s. [2]

At that speed, it would take the Helios probes about 16,949.5 hr = 706.2 days = 1.9 years to reach Pluto, at it’s minimum distance from Earth.

In terms of leaving our solar system, the Voyager 1 is probably the fastest spacecraft, also unmanned, reaching speeds of 17.26km/s, which is a mere 0.0000575c, or 0.00575% the speed of light. Voyager 1 was launched in 1977. [3] Voyager 1 was able to achieve these speeds by gravity slingshot (or gravity assist) which requires a particular alignment of planets that don’t occur that often.

At that speed, it would take Voyager 1 about 68,956.8 hr = 2,873.2 days = 7.9 years to reach Pluto, at it’s minimum distance from Earth.

But Pluto is barely the end of our solar system; far from it. The Oort Cloud defines the outer boundary of our solar system, roughly 50,000 AU (Astronomical Units, where 1AU ? mean distance from the Earth to the Sun) from the Sun, which is roughly one light year. That is, traveling at the speed of light, it would take about a year to reach from Earth.

At Voyager 1’s speeds, this is more like ~18,000 years!

But these are old spacecraft, right? Our spacefaring technology must have improved over the past 40-odd years.

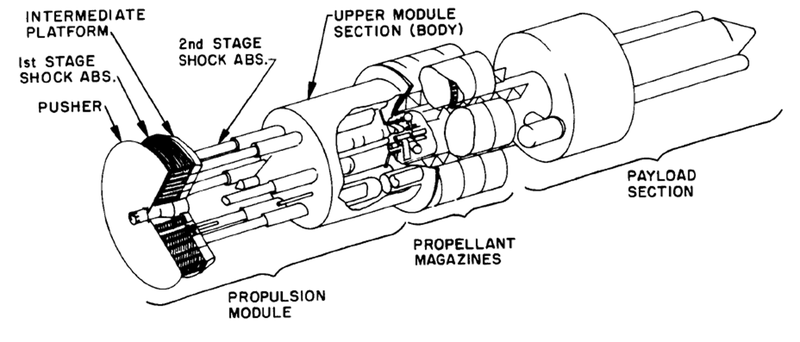

There have been a number of projects trying to improve these speeds. Project Orion is one, started in 1958 and since abandoned, driven by nuclear explosions to propel the craft from behind to speeds ranging from 19 to 31km/s. At it’s best, while in theory it could achieve speeds much greater than the Voyager 1, it still pales against the speed of light. The more recent (mid 2000’s) Mini-Mag Orion seems to be the project’s spiritual successor.

Project Longshot was an endeavor similar to Project Orion from 1988, hoping to achieve impressive speeds of ~13,411km/s, roughly 4.5% the speed of light.

From 1973 to 1978, there was also Project Daedalus, hoping to achieve a maximum speed of 12% the speed of light.

More recently, there is Project Icarus, which started in 2009, functioning as a spiritual successor to Daedalus. There’s also the 100 Year Starship project between DARPA and NASA, which hopes to achieve interstellar travel within the next century.

But in general, these projects are focused on unmanned space travel — probes and other remote-controlled devices. When humans are introduced, a number of other problems crop up, from surviving at those speeds to providing livable environments to protection from cosmic rays and radiation and so on.

And what about other, more sci-fi-esque workarounds and loopholes? What about wormholes and Einstein-Rosen bridges and antimatter rockets and blackholes and so on? There are plenty of those.

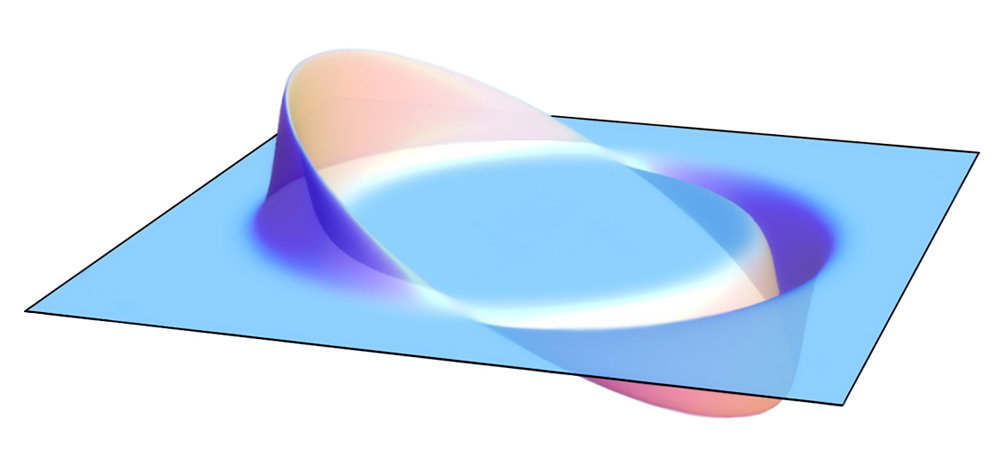

One interesting proposed means of travel is the Alcubierre drive, which is basically like surfing through space. Space is collapsed and expanded on opposing ends such that it forms a “wave”, propelling a “bubble” that contains the spacecraft. The result of this manipulation of space is that the bubble can arrive at another point faster than light, while the spacecraft never exceeds the speed of light within the bubble. But at present, these largely seem to be fantasy, requiring a lot of fragile bits to fit together just right.

If interstellar travel does materialize within our lifetime, I imagine it won’t be as fantastic as science fiction tends to portray it. Perhaps we’ll see great, slow-moving barges or junks transporting large groups of people over multi-generational journeys, but I guess that’s fantastic in it’s own way.