Big Simulation Architecture

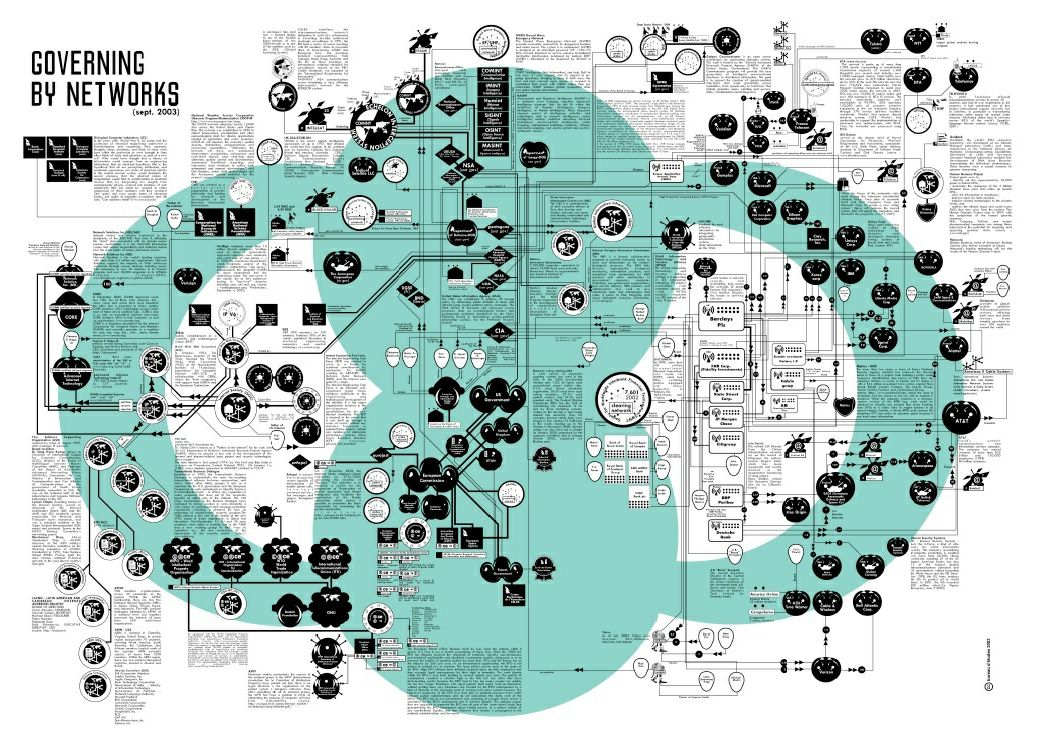

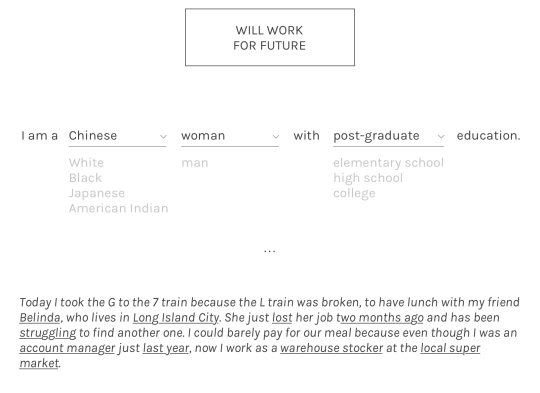

I’ve been interested in extending the work on Humans of Simulated New York into a more general agent-based simulation framework, one that is both accessible to non-technical audiences and powerful enough for more “professional” applications as well. We are all so ill-equipped to contend with the obscenely complex systems we’re a part of, and we end up relying on inadequate (and often damaging) heuristics that cause us to point blame at parties that either have little do with our problems or are similarly victimized by them. Maybe if we had tools which don’t require significant technical training to help us explore these causal rat’s nests, to make this insane interconnectedness more intuitive and presentable, we could think through and talk about these wicked problems more productively.

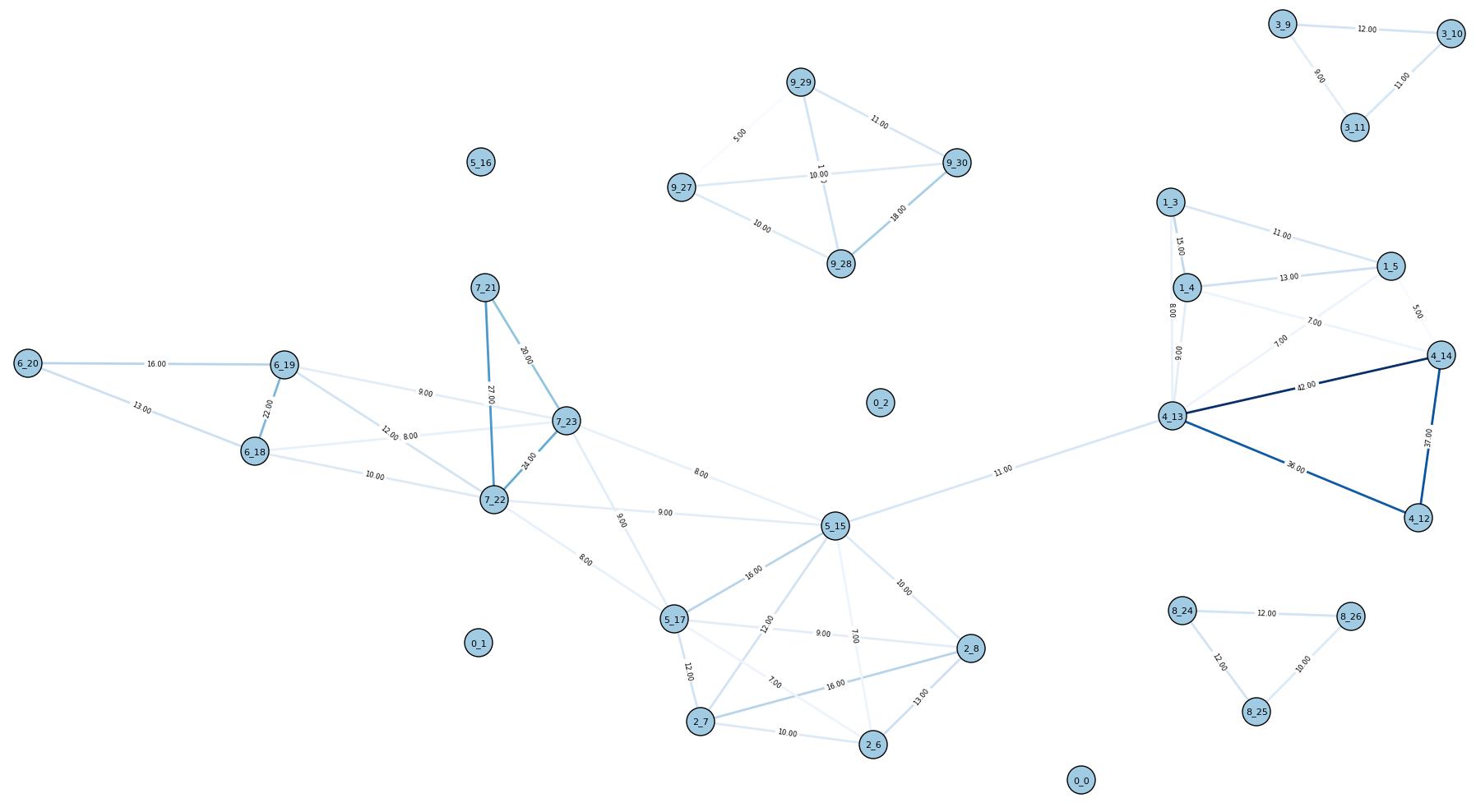

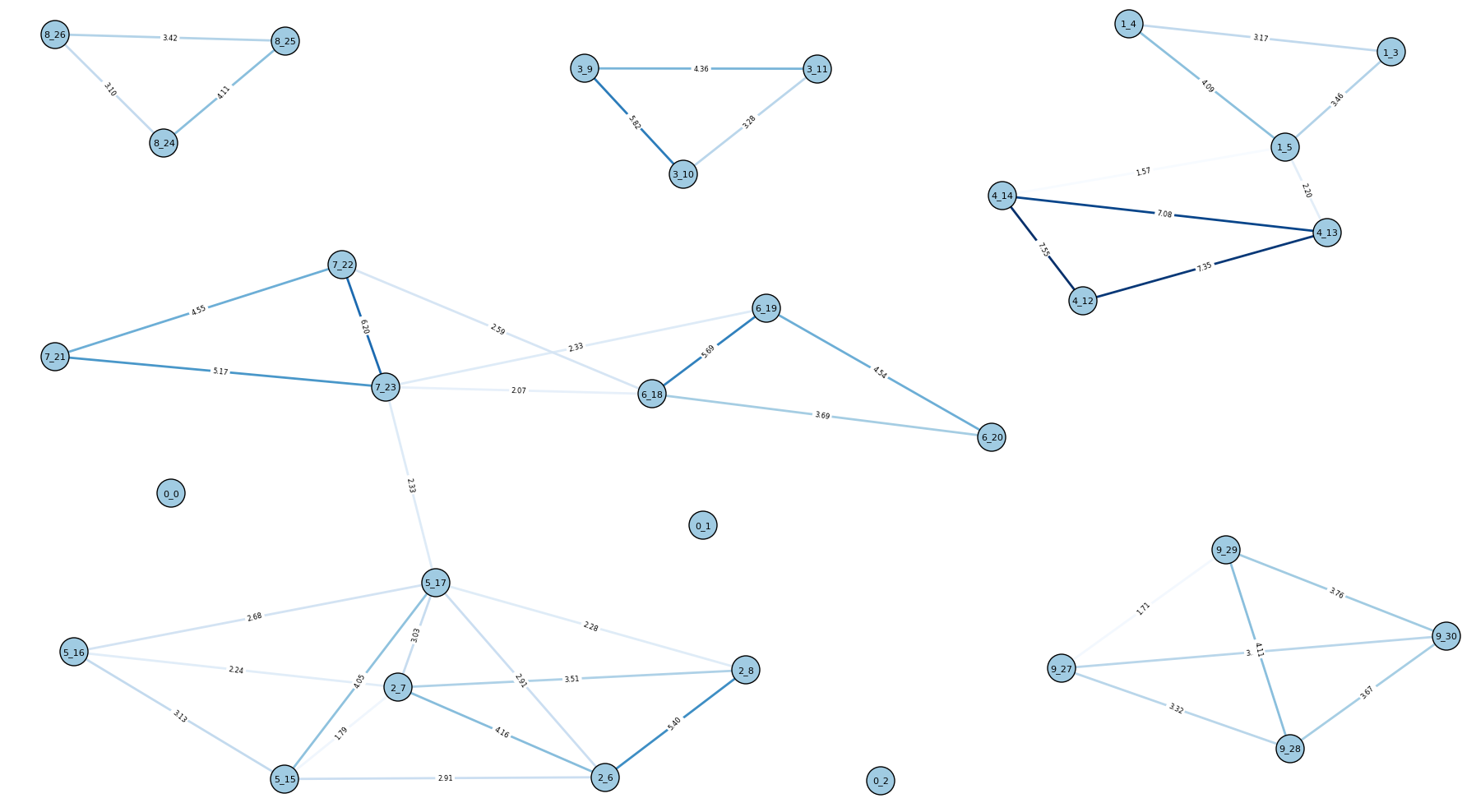

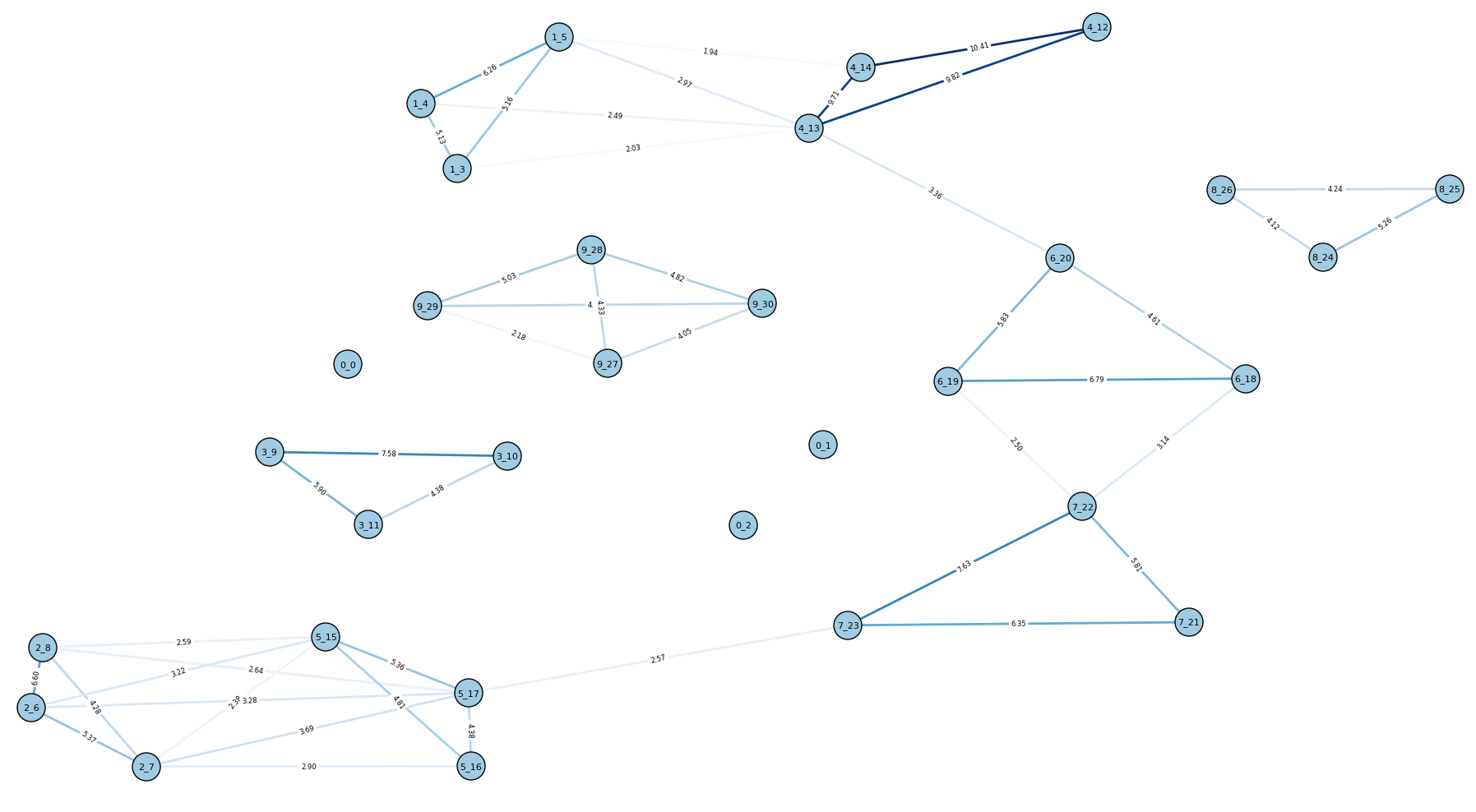

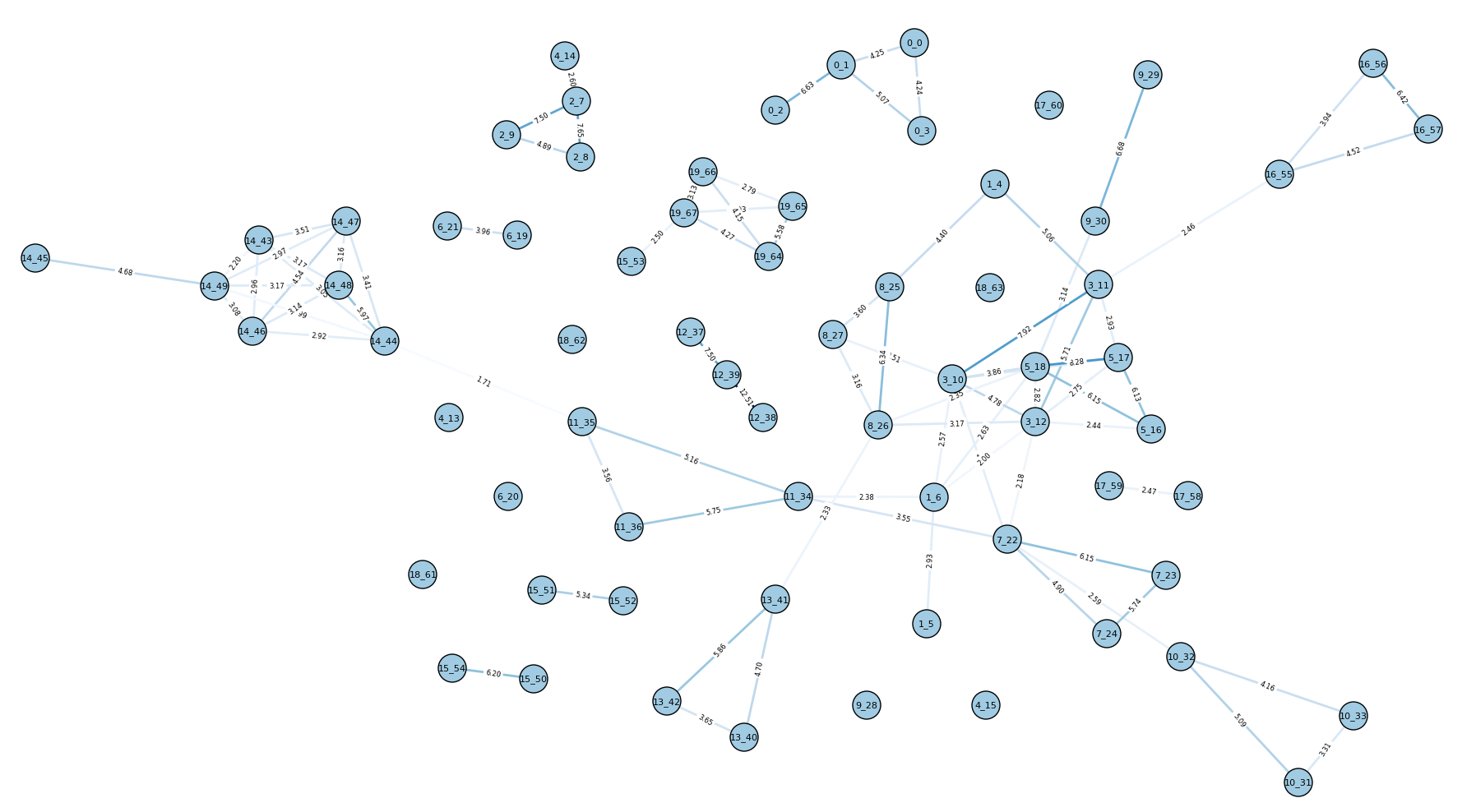

Recently Fei and I started working on a project, tentatively called “system designer” (syd for short), which we hope will provide a foundation for that kind of tooling. syd is currently functional but its features are provisional - I’ve included some examples of visualizations built on top of it, demoing simple models, although it is capable of more sophisticated agent-based models as well.

From an engineering perspective, the goal is to make it easy to write agent-based simulations which may have massive amounts of computationally demanding agents without having to deal with the messiness of parallel and distributed computing.

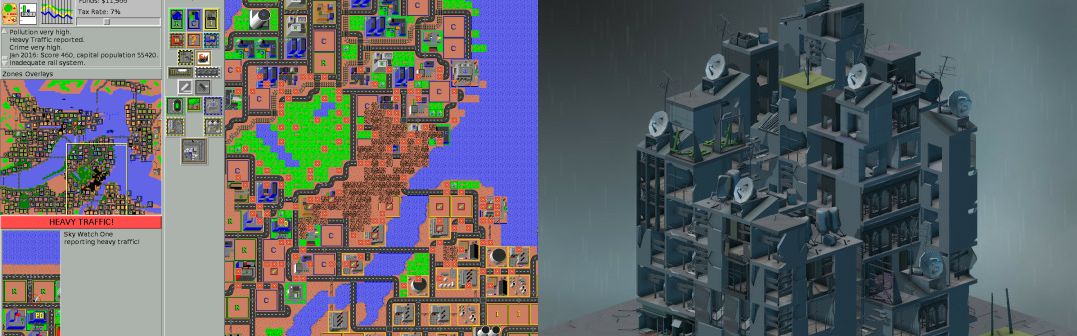

From a design perspective, the goal is to provide interfaces that make defining, running, visualizing, and analyzing such simulations an exploratory experience, almost like a simulation video game (e.g. SimCity).

In both the design and engineering cases there are many interesting challenges.

I’m going to discuss the engineering aspects of the project here and how syd is approaching some of these problems (but bear in mind syd is still in very early stages and may change significantly). At another point I’ll follow-up with more about the design and interface aspects (this is something we’re still sketching out).

syd is built on top of aiomas which handles lower-level details like inter-node communication, so I won’t discuss those here.

(note that at time of writing, not all of what’s discussed here has been implemented yet)

The demands of simulation

If you’re conducting a relatively lightweight simulation, like cellular automata, in which agents are composed of a few simple rules, you can easily run it on a single machine, no problem. The update of a single agent takes almost no time.

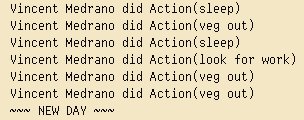

Unfortunately, this approach starts to falter as you get into richer and more detailed simulations. In our first attempts at Humans of Simulated New York, Fei and I designed the agents to be fairly sophisticated - they would have their own preferences and plan out a set of actions for each day, re-planning throughout the day as necessary. Even with our relatively small action space (they could work, look for work, relax, or visit a doctor), this planning process can take quite awhile, especially when it’s executed by hundreds or thousands of agents.

Here you could turn to parallel or distributed methods: you’d take your population of agents, send them to a bunch of different threads or processes or computers (generally referred to as “multi-node” architecture), and then update them in parallel. For example, if you run your simulation across two machines instead of just one, you can almost double the speed of your simulation.

Normally to convert a single-node simulation to a multi-node one you’d have to change up your code to support communication across nodes and a laundry list of other things, but syd abstracts away the difference. You simply instantiate a ComputeSubstrate and you pass in either a single host or a list of hosts. If you pass a single host, the simulation runs in the local process; if a list of hosts, syd transparently runs it as a multi-node simulation:

from syd import ComputeSubstrate single_node = ComputeSubstrate(('localhost', 8888)) multi_node = ComputeSubstrate([ ('localhost', 8888), ('localhost', 8889), ('192.168.1.3', 8888), ('192.168.1.3', 8889)])

Determining where agents go

That’s great, but it doesn’t come for free. Consider a simulation in which each agent must consult a few other agents before deciding what to do. For a single-node (here I’m using a “node” to refer to a single serial process) simulation this communication would happen quickly - all agents are in the same process so there’s basically no overhead to get data from one another.

As soon as we move to the multi-node case we have to worry about the overhead that network communication introduces. The computers we distribute our population across could be on separate continents, or maybe we just have a terrible internet connection, and there may be considerable lag if an agent on one node needs a piece of data from an agent on another node. This network overhead can totally erase all speed gains we’d get from distributing the simulation.

The typical way of managing this network overhead is to be strategic about how agents are distributed across the nodes. For example, if we’re simulating some kind of social network, maybe agents really only communicate with their friends and no one else. In this case, we’d want to put groups of friends in the same process so they don’t have to go over the network to communicate, and we’d effectively eliminate most of the network communication.

The problem here (maybe you’re starting to see a pattern) is that there is no one distribution strategy that works well for all conceivable agent-based simulations. It really depends on the particular communication patterns that happen within the simulation. In the literature around engineering these agent-based systems you’ll see mention of “spheres of influence” and “event horizons” which determine how to divide up a population across nodes. Agents that are outside of each other’s spheres of influence or beyond each other’s event horizons are fair game to send to different nodes. Unfortunately what exactly constitutes a “sphere of influence” or “event horizon” varies according to the specifics of your simulation.

In syd, if you create a multi-node substrate you can also specify a distribution strategy (a Distributor object) which determines which agents are sent to which nodes. So far there are only two strategies:

syd.distributors.RoundRobin: a naive round robin strategy that just distributes agents sequentially across nodes.syd.distributors.Grid2DPartition: if agents live in a grid, this recursively bisects the grid into “neighborhoods” so that each neighborhood gets its own node. This is appropriate when agents only communicate with adjacent agents (e.g. cellular automata). Network communication still happens at the borders of neighborhoods, but overall network communication is minimized.

You can also define your own Distributor for your particular case.

from syd import ComputeSubstrate, distributors multi_node = ComputeSubstrate([ ('localhost', 8888), ('localhost', 8889), ('192.168.1.3', 8888), ('192.168.1.3', 8889)], distributor=distributors.RoundRobin)

There is yet another problem to consider - in some simulations, agents may be mobile; for example, if we’re simulating a grid world, we may distribute agents according to where in the grid they are (e.g. with the Grid2DPartition distributor), but what if they move to another part of the grid? We might want to move them to the node that’s running that part of the grid. But if this happens a lot, now we’ve introduced a ton of overhead shuffling agents from node to node.

As another example - if the topology of the simulation is a social network instead of a grid, such that they are communicating most with their friends, what happens if those relationships change over time? If they become friends with agents on another node, should we re-locate them to that node? Again, this will introduce extra overhead.

I haven’t yet come up with a good way of handling this.

Race conditions and simultaneous updates

There is yet another problem to consider. With a single-node simulation, agents all update their states serially. There is no fear of race conditions: we don’t have to worry about multiple agents trying to simultaneously access a shared resource (e.g. another agent) and making conflicting updates or out-of-sync reads.

This is a huge concern in the multi-node case, and the way syd works around it is to separate agent updates into two distinct phases:

- the

decidephase, a.k.a. the “observation” or “read” phase, where the agent collects (“observes”) the information it needs from other agents or the world and then decides on what updates to make (but it does not actually apply the updates). - the

updatephase, a.k.a. the “write” phase, where the agent applies all queued updates.

So in the decide phase, agents queue updates for themselves or for other agents as functions that mutate their state. This has the effect of agents simultaneously updating their states, as opposed to updating them in sequence.

Unfortunately, this structure does not entirely solve our problems - it is possible that there are conflicting or redundant updates queued for an agent, and those usually must be dealt with in particular ways. I’m still figuring out a good way to manage this.

Node failures

Another concern is the possibility of node failure. What if a machine dies in the middle of your simulation? All the agents that were on that machine will be lost, and the simulation will become invalid.

The approach that I’m going to try is to snapshot all agent states every ¦n¦ steps (to some key-value store, ideally with some kind of redundancy in the event that one of those nodes fail!). If a node failure is detected, the simulation supervisor will automatically restart the simulation from the last snapshot (this could involve the spinning up of a new replacement machine or just continuing with one less machine).

Abstract the pain away

Long story short: parallel and distributed computing is hard. Fortunately for the end-user, most of this nasty stuff is hidden away. The plan is to include many “sensible defaults” with syd so that the majority of use-cases do not require, for example, the implementation of a custom Distributor, or any other messing about with the internals. You’ll simply indicate that you want your simulation to run on multiple computers, and it’ll do just that.

References

- Antelmi, A., Cordasco, G., Spagnuolo, C. & Vicidomini, L. (2015). On Evaluating Graph Partitioning Algorithms for Distributed Agent Based Models on Networks. European Conference on Parallel Processing.

- Bharti, R. (2016). HIVE - An Agent Based Modeling Framework. Master’s Projects.

- Chenney, S. (2001). Simulation Level-of-Detail. Game Developers Conference.

- Chenney, S. Simulation Culling and Level-of-Detail. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications.

- Chenney, S., Arikan, O. & Forsyth, D. (2001). Proxy Simulations for Efficient Dynamics. EUROGRAPHICS.

- Chris Rouly, O. (2014). Midwife: CPU cluster load distribution of Virtual Agent AIs. Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS).

- He, M., Ruan, H. & Yu, C. (2003). A Predator-Prey Model Based on the Fully Parallel Cellular Automata. International Journal of Modern Physics C.

- Holcombe, M., Coakley, S., Kiran, M., Chin, S., Greenough, C., Worth, D., Cincotti, S., Raberto, M., Teglio, A., Deissenberg, C., van der Hoog, S., Dawid, H., Gemkow, S., Harting, P. & Neugart, M. (2013). Large-Scale Modeling of Economic Systems. Complex Systems, 22.

- K. Bansal, A. (2006). Incorporating Fault Tolerance in Distributed Agent Based Systems by Simulating Bio-computing Model of Stress Pathways. Proceedings of SPIE, 6201.

- K. Som, T. & G. Sargen, R. (2000). Model Structure and Load Balancing in Optimistic Parallel Discrete Event Simulation. Proceedings of the Fourteenth Workshop on Parallel and Distributed Simulation.

- Kim, I., Tsou, M. & Feng, C. (2015). Design and implementation strategy of a parallel agent-based Schelling model. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 49(2015), pp. 30-41.

- Kubalík, J., Tichý, P., Šindelář, R. & J. Staron, R. (2010). Clustering Methods for Agent Distribution Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews).

- Lees, M., Logan, B., Oguara, T. & Theodoropoulos, G. (2004). Simulating Agent-Based Systems with HLA: The Case of SIM_AGENT - Part II. International Conference on Computational Science.

- Logan, B. & Theodoropoulos, G. (2001). The Distributed Simulation of Multi-Agent Systems. Proceedings of the IEEE, 89(2).

- Lysenko, M. & M. D’Souza, R. (2008). A Framework for Megascale Agent Based Model Simulations on Graphics Processing Units. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simluation, 11(4/10). http://jasss.soc.survey.ac.uk/11/4/10.html.

- Márquez, C., César, E. & Sorribes, J. (2015). Graph-Based Automatic Dynamic Load Balancing for HPC Agent-Based Simulations. European Conference on Parallel Processing.

- Navarro, L., Flacher, F. & Corruble, V. (2011). Dynamic Level of Detail for Large Scale Agent-Based Urban Simulations. Proceedings of 10th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, pp. 701-708.

- Oey, M., van Splunter, S., Ogston, E., Warnier, M. & M.T. Brazier, F. (2010). A Framework for Developing Agent-Based Distributed Applications. BNAIC 2010: 22rd Benelux Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Pleisch, S. & Schiper, A. (2000). Modeling Fault-Tolerant Mobile Agent Execution as a Sequence of Agreement Problems. Reliable Distributed Systems.

- Richiardi, M. & Fagiolo, G. (2014). Empirical Validation of Agent-Based Models.

- Rousset, A., Herrmann, B., Lang, C. & Philippe, L. (2015). A communication schema for parallel and distributed Multi-Agent Systems based on MPI. European Conference on Parallel Processing.

- Rubio-Campillo, X. (2014). Pandora: A Versatile Agent-Based Modelling Platform for Social Simulation. SIMUL 2014: The Sixth International Conference on Advances in System Simulation.

- Scheutz, M. & Schermerhorn, P. (2006). Adaptive Algorithms for the Dynamic Distribution and Parallel Execution of Agent-Based Models. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing.

- Sunshine-Hill, B. (2013). Managing Simulation Level-of-Detail with the LOD Trader. Motion in Games.

- Tsugawa, S., Ohsaki, H. & Imase, M. (2012). Lightweight Distributed Method for Connectvity-Based Clustering Based on Schelling’s Model. 26th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops.

- Vecchiola, C., Grosso, A., Passadore, A. & Boccalatte, A. (2009). AgentService: A Framework for Distributed Multi-Agent System DEvelopment. International Journal of Computers and Applications, 31(3), pp. 204-210.

- Dubitzky, W., Kurowski, K., & Schott, B, eds. (2012). Large-Scale Computing Techniques for Complex System Simulations.