Social Simulation Components: Social Contagion

The idea of syd is that it will be geared towards social simulation - that is, modeling systems that are driven by humans (or other social beings) interacting. To support social simulations syd will include some off-the-shelf models that can be composed to define agents with human-ish behaviors.

One category of such models are around the propagation and mutation of ideas and behaviors (“social contagion”). Given a population of agents with varying cultural values, how do these values spread or change over time? How do groups of individuals coalesce into coherent cultures?

What follows are some notes on a small selection of these models.

Sorting & peer effects

Two primary mechanisms are sorting, or “homophily”, the tendency to associate with similar people, and peer effects, the tendency to become more like people we are around often.

Schelling’s model of segregation may be the most well-known example of a sorting model, where residents move if too many of their neighbors aren’t like them.

A very simple peer effect model is Granovetter’s model. Say there is a population of ¦N¦ individuals and ¦n¦ of them are involved in a riot. Each individual in the population has some threshold ¦T_i¦; if over ¦T_i¦ people are in the riot, they’ll join the riot too. Basically this is a bandwagon model in which people will do whatever others are doing when it becomes popular enough.

Granovetter’s model does not incorporate the innate appeal of the behavior (or product, idea, etc), just how many people are participating in it. One could imagine though that the riot looks really exciting and people join not because of how many others are already there, but because they are drawn to something else about it.

A simple extension of Granovetter’s model, the Standing Ovation model, captures this. The behavior in question has some appeal or quality ¦Q¦. We add some additional noise to ¦Q¦ to get the observed “signal” ¦S = Q + \epsilon¦. This error allows us to capture a bit of the variance in perceived appeal (some people may find it appealing, some people may not, the politics around the riot may be very complex, etc). If ¦S > T_i¦, then person ¦i¦ participates. After assessing the appeal, those who are still not participating then have the Granovetter’s model applied (they join if enough others are participating).

There are further extensions to the Standing Ovation model. You could say that an agent’s relationships affects their likelihood to join, e.g. if I see 100 strangers rioting I may not care to join, but if 10 of my friends are then I will.

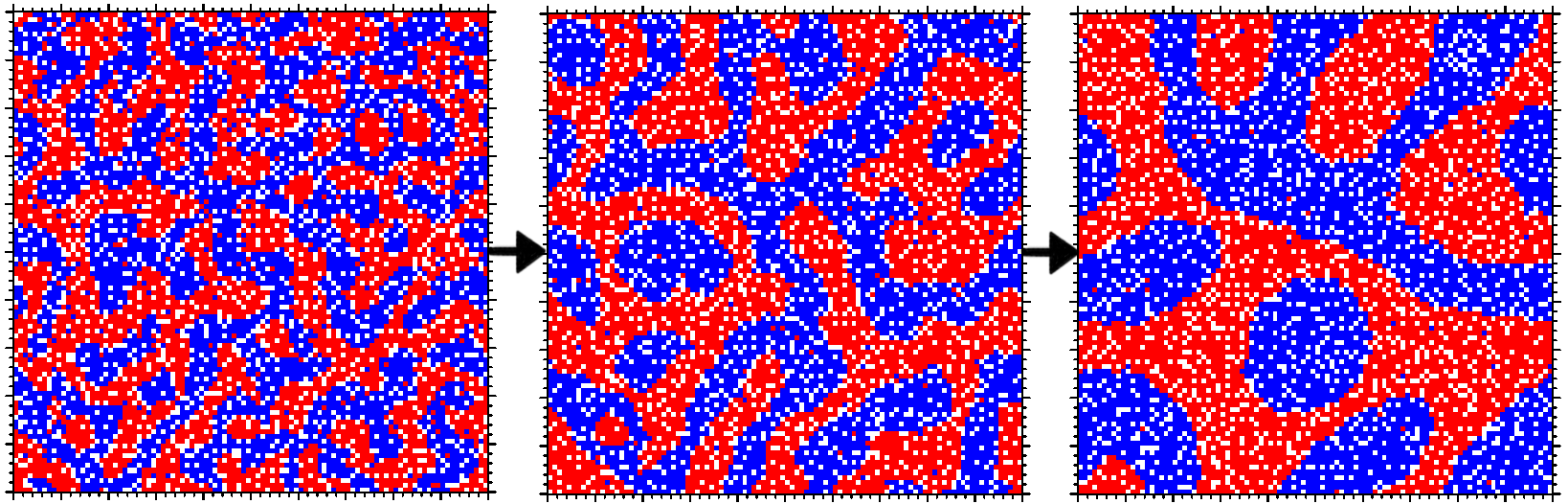

Axelrod’s culture model

Axelrod’s culture model is a simple model of how a “culture” (a population sharing many traits, beliefs, behaviors, etc) might develop.

- each individual is described by a vector of traits

- the population is placed in some space (e.g. a grid or a social network)

- an individual interacts with a neighbor with some probability based on their trait similarity

- if they interact, pick one trait and match with the neighbor’s

This model can be extended with a consistency rule: sometimes the value of one trait is copied over to another trait (in the same individual), this models the two traits becoming consistent. For example, perhaps the changing of one belief causes dependent beliefs to change as well, or requires beliefs it’s dependent on to change.

Traits can also randomly change as well due to “error” (imperfect imitation or communication) or “innovation”.

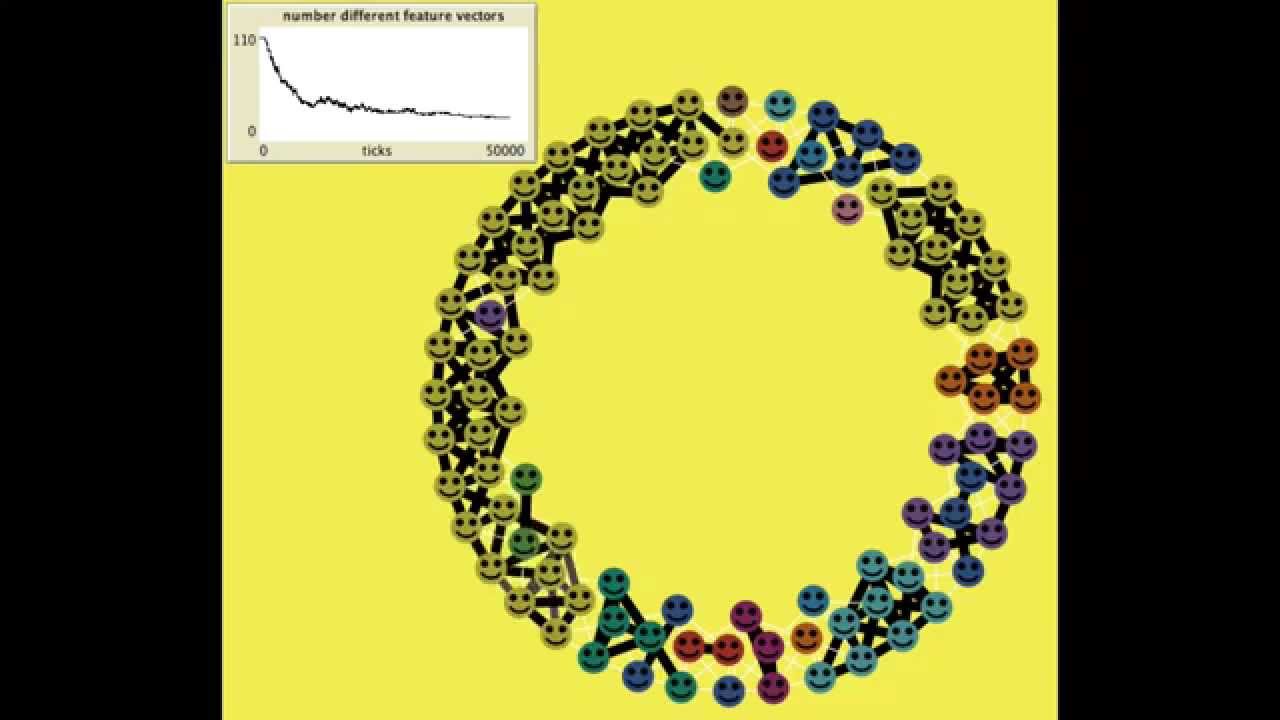

Modeling opinion flow with Boids

A really interesting idea is to apply the Boids flocking algorithm to the modeling of idea dissemination (if you’re unfamiliar with Boids, Craig Reynolds explains here).

Here agents form a directed graph (e.g. a social network), where edges have two values: frequency of communication and respect one agent holds for the other. For each possible belief, agents have an alignment score which can have an arbitrary scale, e.g. -3 for strong disbelief to 3 for strong belief.

The agent feels a “force” that causes them to change their own alignment. This force is the sum of force from alignment, force from cohesion, and force from separation.

- force from alignment is computed by the average alignment across all agents - this is the perceived majority opinion.

- force from cohesion: each agent computes the average alignment felt by their neighbors they respect (i.e. respect is positive), weighted by their respect for those neighbors.

- force from separation: like the force from cohesion, but computed across their neighbors they disrespect (i.e. respect is negative), weighted by their respect for those neighbors.

This force is normalized and is used to compute a probability that the individual changes their alignment one way or the other. We specify some proportionality constant ¦\alpha¦ which determines how affected an agent is by the force. For force ¦F¦ the probability of change of alignment is just ¦\alpha F¦. It’s up to the implementer how much an agent’s alignment changes.

Memetics

A meme is an idea/belief/etc that behaves according to the rules of memetics, which models the spread of ideas by applying evolutionary concepts:

- phenotypes & alleles

- the “offspring” of a meme vary in their “appearance”

- a meme contains characteristics (“alleles”), some of which are transmitted to their child

- variability in allele combinations is responsible for variability at the phenotypic level

- mutation

- idea mutation may be random

- or it may happen for a reason; ideas can change – to solve problems, for instance (these mutations are essentially innovations advocated by a change agent)

- selection

- some ideas are more likely to survive than others

- an idea’s survival is based on how “fit” it is

- an idea’s measure of fitness is the likelihood of its offspring surviving long enough to produce their own offspring, compared to other memes

- Lamarckian properties

- unlike biological evolution, members can be modified, activated or deactivated within a generation (people can adapt their ideas to deal with new information, for example)

- drift

- if multiple finite-sized populations exist, beginning w/ the same set of initial conditions & operate according to the same mechanisms/constraints, completely different sets of ideas can emerge b/w the populations

- this drift is due to sampling error when a parent meme produces offspring (random allele heritage)

Memetic transmission may be horizontal (intra-generational) and/or vertical (intergenerational).

The primary mechanism for memetic transmission is imitation, but other mechanisms include social learning and instruction.

Note that the transmission of an idea is heavily dependent on its own characteristics.

For example, there are some ideas that have “mutation-resistant” qualities, e.g. “don’t question the Bible” (though that does not preclude them from mutation entirely).

Some ideas also have the attribute of “proselytism”; that is part of the idea is the spreading of the idea.

The Cavalli-Sforza Feldman model is a memetics model describing how a population of beliefs evolve over time.

There is a transmission function:

$$ p = 1 - |1 - g|^{n \mu_t} $$

where:

- ¦p¦ is the probability that an individual’s belief state will be transformed (i.e. imitate another’s) after ¦n¦ contacts

- ¦g¦ is the probability of transformation after each contact

- ¦\mu_t¦ is the proportion of people the individual can come into contact with who already have the target belief state

There’s also a selection function:

$$ \mu_t’ = \frac{\mu_t (1+s)}{1 + s \mu_t} $$

where:

- ¦\mu_t’¦ is the proportion of beliefs that survive selection for a single generation

- ¦\mu_t¦ is the proportion of beliefs before selection

- ¦s¦ is the degree of fitness

“The popular enforcement of unpopular norms”

The models presented so far make no distinction between public and private beliefs, but it’s very clear that people often publicly conform to ideas that they may not really feel strongly about. This phenomenon is called pluralistic ignorance: “situations where a majority of group member privately reject a norm but assume (incorrectly) that most others accept it”.

It’s one thing to publicly conform to ideas you don’t agree with, but people often go a step further and try to enforce others to comply to these ideas. Why is that?

The “illusion of transparency” refers to the tendency where people believe that others can read more about their internal state than they actually can. Maybe something embarrassing happened and you feel as if everyone knows, even if no one possibly could. In the context of pluralistic ignorance, this tendency causes people to feel as though others can see through their insincere alignment with the norm, so they take additional steps to “prove” their conviction.

The Emperor’s Dilemma: A Computational Model of Self‐Enforcing Norms proposes the following model for this phenomena:

- each agent ¦i¦ has a binary private belief ¦B_i¦ which can be 1 (true believer) or -1 (disbeliever).

- true enforcement is when a true believer/disbeliever enforces others to comply/oppose

- false enforcement is when a false believer enforces others to comply

An agent ¦i¦ choice to comply with the norm is ¦C_i¦. If ¦C_i=1¦ the agent chooses to complex, otherwise ¦C_i=-1¦. This choice depends on the strength of the agent’s convictions ¦0 < S \leq 1¦.

A neighbor ¦j¦’s enforcement of the norm is represented as ¦E_j=1¦; if they enforce deviance instead then ¦E_j=-1¦. Thus we can compute ¦C_i¦ as:

$$ C_i = \begin{cases} -B_i & \text{if } \frac{-B_i}{N_i} \sum_{j=1}^{N_i} E_j > S_i \ B_i & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$

We assume that true believers (¦B_i = 1¦) have maximal conviction (¦S_i = 1¦) and so are resistant to neighbors enforcing deviance.

The enforcement of an agent ¦i¦ is computed:

$$ E_i = \begin{cases} -B_i & \text{if } (\frac{-B_i}{N_i} \sum_{j=1}^{N_i} E_j > S_i + K) \land (B_i \neq C_i) \ +B_i & \text{if } (S_i W_i > K) \land (B_i = C_i) \ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$

where ¦0 < K < 1¦ is an additional cost of enforcement for those who also comply (it is ¦K¦ more difficult to get someone who does not privately/truly align with the belief to enforce it).

¦W_i¦ is the need for enforcement, which is the proportion of agent ¦i¦’s neighbors whose behavior does not confirm with ¦i¦’s beliefs ¦B_i¦:

$$ W_i = \frac{1- (B_i/N_i) \sum_{j=1}^{N_i} C_j}{2} $$

Agents can only enforce compliance or deviance if they have complied or deviated, respectively.

The model can be extended by making it so that true disbelievers can be “converted” to true believers (i.e. their private belief changes to conform to the public norm).

References

- Model Thinking. Scott E. Page.

- Cole, S. (2006, September 28). Modeling opinion flow in humans using boids algorithm & social network analysis. Gamasutra - The Art & Business of Making Games.

- Simpkins, B., Sieck, W., Smart, P., & Mueller, S. (2010). Idea Propagation in Social Networks: The Role of ‘Cognitive Advantage’. Network-Enabled Cognition: The Contribution of Social and Technological Networks to Human Cognition.

- Centola, D., Willer, R., & Macy, M. (2005). The Emperor’s Dilemma: A Computational Model of Self‐Enforcing Norms. American Journal of Sociology, 110(4), 1009-1040.