Chaos and Reductionism

I’ve been thinking more about complexity and came across a great Stanford lecture by Professor Robert Sapolsky titled Chaos and Reductionism which introduces the concept of complexity by contrasting it with the reductionist approach to analyzing systems; this is a big note dump for that lecture:

Reductionism — the foundational (Western) scientific idea that, if you want to understand a complex system, break it down (reduce it) to its component parts. When you understand its individual parts, you will be able to understand the system. There are implicit notions of additive and linear natures to the combination of these parts — that you add the parts together and they will increase in their complexity in a linear manner which leads to the complex system.

With this approach, you could see the starting state of a system and predict its final, mature state/consequence (or work backwards from its final state to its starting state), without having to go step-by-step. That is, extrapolation — using rules to predict similar cases beyond just the present case (where the rules were first observed).

There’s also the concept of a “blueprint”, that is, there’s some expectation of what you expect to see when you extrapolate.

Another important aspect of reductionism is that there is variability. For instance, amongst people, there’s an average body temperature but some variability in the specific values across individuals. What do you make of variability? Reductionism takes variability as noise — something to be gotten rid of or avoided. “Instrument” error, where “instrument” ranges from a person’s observation to machinery. To mitigate this, reductionism believes that further reduction will reduce this noise. The closer you are, the more you’ll be able to see what’s actually going on. So, the better you get at getting down to the details — through new techniques or equipment — there will be less variability.

“At the bottom of all these reductive processes, there is an iconic and absolute and idealized norm as to what the answer is. If you see anybody not having [a body temperature of] 98.6, it’s because there’s noise in your measurement systems — variability is noise, variability is something to get rid of, and the way to get rid of variability is to become more reductive. Variability is discrepancy from seeing what the actual true measure is.”

Reductionism has been the driving force behind science — coming up with new techniques or equipment to measure things more closely so we can see how things “truly” work.

For instance — if you want to understand how the body works, you need to understand how organs work, and to understand how organs work, you need to understand how cells work, etc, until you get all the way to the bottom. And then once you understand the bottom, you add everything back up and now you understand the body. But this approach is problematic — biology, and certainly plenty of other systems, don’t work that way.

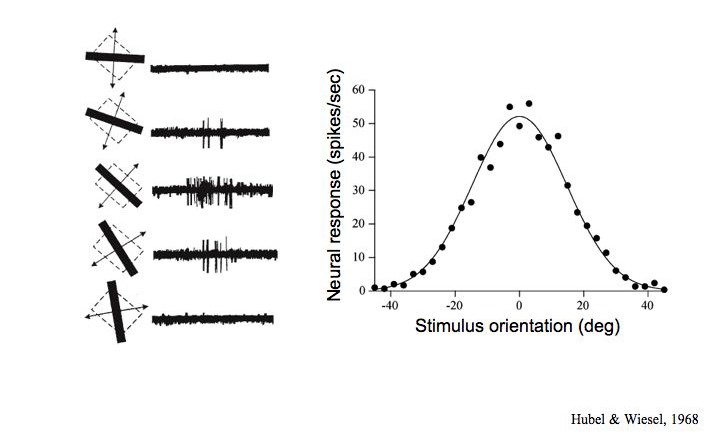

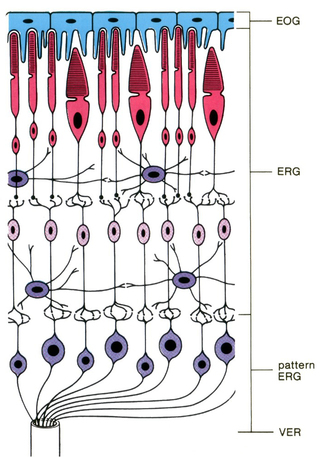

In neurobiology, two major researchers (Hubel and Wiesel) came up with a reductionist explanation of how the cortex works; they found that there were individual cells in the retina which connected directly to neurons in the cortex, that you could trace the starting state (which retina cell has been stimulated) to the ending state (which neuron fires) directly (a point-for-point relationship). In this most basic layer of the cortex, neurons could recognize a dot and one dot only, and it was the only neuron that could recognize it. And in the next layer, those neurons can recognize a particular line at a certain angle, and other neurons would recognize those lines at different angles, etc. So using the same reductionism behind the retina=>neuron=>dot, you can extrapolate to retina=>neuron=>dot=>line. And then the next layer, you have neurons that can recognize a particular curve. If you know what’s going on at any of these other levels, you can trace that state to the other states (i.e. what’s going on at the other levels). And it was believed that you could continue to extrapolate in this way — that there’s a particular neuron responsible for a particular arrangement of sensory information. Above that curve layer would be neurons that recognize particular sets of curves, and so on. Eventually towards the top you’d have a neuron that would recognize your grandmother’s face from a particular perspective/at a particular angle.

But no one has ever been able to demonstrate the widespread existence of the “ grandmother neuron“. There are very few “ sparse coding” neurons (“sparse coding” meaning you only need a few neurons to recognize some complex thing) which are similar, i.e. a single neuron that responds to a face, and only a specific type of face — there was a rather bizarre study where these upper levels were studied in Rhesus monkeys, and they found a single neuron which would only respond to pictures of Jennifer Aniston, and if that wasn’t strange enough, the only other thing they would respond to was an image of the Sydney Opera House.

If you think about it, the number of necessary neurons at each level increases quite a bit for each level. At the lowest level, you have 1:1 neurons for retina cells (to recognize dots). But then, if you have a neuron for each line at each angle formed by these dots — that’s a lot more neurons (“orientation selectivity”; there are many ways for lines to be oriented). And this happens at every level — so there just simply aren’t enough neurons in visual cortex (and the brain) to represent everything. So this reductionism falls apart here.

In this case, the new approach involves the idea of neural networks. Complex information isn’t encoded in single neurons, but rather in patterns of activation across multiple neurons — i.e. networks of neurons.

Bifurcating Systems

A bifurcating system is a branching system — each branch keeps splitting off into more branches — which is “scale free”. Viewing the system at one level looks just like viewing the system at another level (i.e. it is “scale free”). It has the nature of a fractal.

The circulation system is an example of this, so is the pulmonary system, and so are neurons. How does the body code for the creation of a bifurcating system? The reductionist approach might come to theorize that there’s some gene that codes, for example, when an aorta bifurcates (splits into two), and then a different gene that specifies the next bifurcation, etc. But again, there aren’t enough genes to code this way.

Randomness

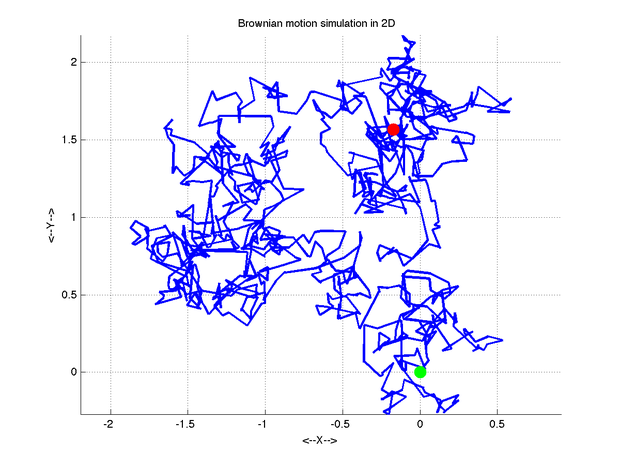

In the development of biological systems, there is a degree of chance involved. For instance, Brownian (random) motion at the molecular level causes cells to split with uneven distributions of mitochondria, which interferes with the reductionist characteristic of being able to trace a system from its start to its final state.

There was a study trying to predict the dominance hierarchy that would emerge from a particular starting configuration of fish. First, the dominance hierarchy of a group of fish was established by using a round-robin technique; that is, pairing each fish off with one another, seeing which one dominates, and then generating the hierarchy by inferring that the first that dominated every round is the top fish, the one that dominated the second most is the next in the hierarchy, etc. Then the fish were released together to see how predictive this hierarchy was of natural conditions. The hierarchy had zero predictability for what actually happened. The fish can calculate to some degree logical outcomes of social interactions, and uses this ability to strategize their own behavior. However, this necessitates that they observe these social interactions to begin with, and that is largely left to chance: they could be looking in the wrong direction, and miss out on the information to strategize on.

A Taxonomy of Systems

So there are systems which, after some level, are non-reductive . They are non-additive and non-linear . Chance and sheer numbers of possible outcomes are characteristic of these systems. These systems are “chaotic” systems, and they are beyond this reductionist framework.

There are deterministic systems — those in which predictions can be made.There are periodic deterministic systems, which have rules consistent in such a way that you can directly calculate some later value, without having to calculate step-wise to that value; they are linear. That consistency provides an ease of predictability; you can rest assured that the rule holds in an identical manner for the entire sequence. These systems are reductive; the reductionist approach works here. There is a pattern which repeats (i.e. is periodic).

For example:1,2,3,4,5 has a rule of “+1”; it is very easy to answer: what’s the 15th value?In contrast, aperiodic deterministic systems are much more difficult to project in this way. There are rules to go from one step to another, like in periodic deterministic systems, but you need to calculate predictions stepwise, figuring out one value, then applying the rule again to figure out the next, ad nauseum. There aren’t repeating patterns — although there’s a consistent rule that governs each step, the relationship between each step is inconsistent. Arbitrary values in a sequence, for example, cannot be derived from the rules without manually calculating each preceding value in the sequence.

There are nondeterministic systems, where the steps are random; there is no consistent rule. The nature of one value does not determine the subsequent value. Chaotic systems are often taken to be nondeterministic systems, but they are not.

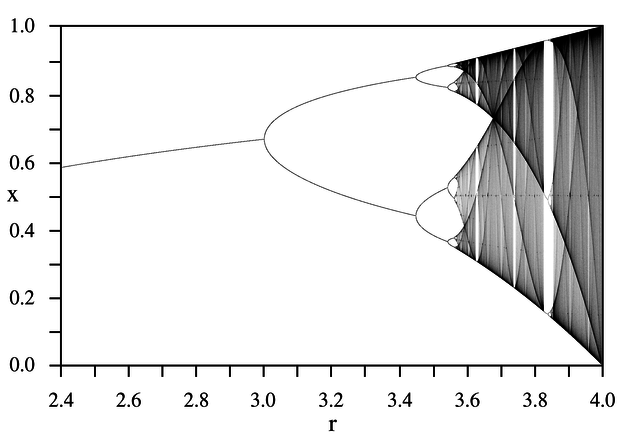

Chaotic systems, have rules for each step, but the relationship for each step is non-linear, they’re not identical. That is, they are aperiodic deterministic systems. There is no pattern which repeats. So the only way to figure out any value in such a sequence is to calculate step-wise to that position. So, you can figure out the state of the system in the future, but it’s not “predictable” in the same way that periodic deterministic systems are.

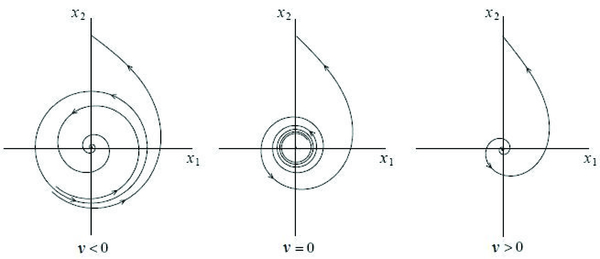

Reductive, periodic deterministic systems can reach a tipping point, when enough force is applied to them, where they break down and become chaotic, aperiodic deterministic systems. Periodic systems are in an equilibrium, such that, if you disturb the system temporarily, it will eventually reset back into that periodic equilibrium. This is called an “ attractor“. This point of equilibrium would be considered the “true” answer of such a system.

In this image, you can see the circle in the center is the attractor, and the system spirals back to it.

Chaotic systems, on the other hand, have no equilibrium to reset back to. They will oscillate infinitely. So they are unpredictable in this sense. This is called a “ strange attractor“. There is no “true” answer here because there is no stable settling point that could be considered one. Rather, the entire fluctuation, the entire variability, could be considered the “true” answer — the system itself.

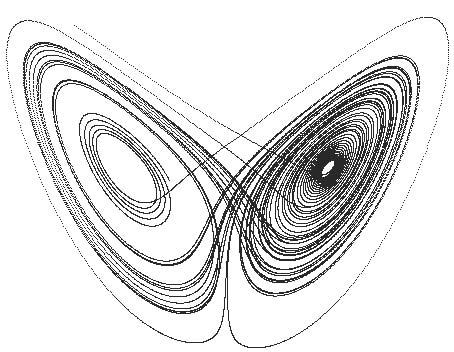

Here you can see the strange attractor, which is never reached, and the system just fluctuates constantly.

But if you’re measuring the system, it can be very deceiving. Say you take a measurement and it’s on one of these points. Say it’s (6, 3). And you want to try and predict what the next point is be. And you calculate the next point, and so on, and then you return to your starting point, and you think, oh — it’s not chaotic at all, it’s periodic! But if you look closer, you see that this isn’t the case. You started on (6, 3.7), and now you’ve ended up on (6, 3.8). It’s not actually the same point.

Or, to give a better example, you actually started on (6.38791587129873918751982739172398179872147), and the second time around, you’ve actually landed on (6.38791587129873918751982739172398179872148). The numbers are very close, but they are not the same. They are variable. And thus the next point after each is different, and the path after the new point is completely different from the path after the starting point. The tiny little difference gets amplified step by step by step — the “ butterfly effect“. So these systems become practically unpredictable as a result.

No matter how good your reductive tools are, no matter how accurate your measurements and techniques are, that variability is always there. In this sense, such chaotic systems are scale-free: no matter how closely you look, no matter what level you’re looking at, that variability is there, and its effects will be felt. This undermines the reductionist approach which dictates that the closer you look at a system, the less noise you will have, and the better and truer understanding you will have of it. But it’s not noise resulting from technique or measurement inadequacy — it is part of the phenomenon, it is a characteristic of the system itself.

Fractals

Here’s where fractals come in.

A fractal is information that codes for a pattern, a line in particular, which is one-dimensional, but this line has an infinite amount of complexity, such that, if you look closer and closer at the line, you still see that complexity. So it is infinitely long, but in a finite space, and it starts to seem more like a two-dimensional object. But it isn’t! A fractal is an object or property that is a fraction of a dimension. It’s not quite two-dimensional, but it’s also more than one-dimensional — it’s somewhere in between.Fractals can also be described more simply as something that is scale-free: at any level you look at it, the variability is the same.

The bifurcating systems mentioned earlier are fractals. And, rather than having their branching coded explicitly by genes, for example, they are governed by a scale-free rule.

Does this matter in practice?

Sapolsky (the lecturer) and a student performed a study where they took some problem in biology — the effect of testosterone in behavior — and gathered every study approach this problem from different levels: at the level of society, the individual, the cell, testosterone, etc. For each study they gathered the results and calculated a coefficient of variation, which is the percentage of your result that variation represents.

For example, if I have a measurement of 100 with +/- 50, then the coefficient of variation is 50%.

Then you can take the average coefficient of variation across each level.

If the reductionist argument holds, then you should see a decreasing coefficient of variation — that is, a decreasing of noise — as you move from broad to narrow. But there is no such trend.

But what if there was noise in their own measurements? That a lot of the papers they surveyed weren’t very good, perhaps sloppily measured or something. So they looked at the number of times cited as an indicator of the paper’s quality, and re-did the analysis (the 10% papers by this metric). But the results were the same.

It isn’t that reductionism is not useful. It is still very useful. It is a lot simpler, and while it isn’t completely “accurate”, that is, there is room for error, it can still paint broader strokes that is still actionable and reflective of the world.

For instance, if I want to test the efficacy of a vaccine, I don’t want to get down to the level of each individual and see how it works, I’d want to be a bit broader and say, ok, this group got the vaccine, this one didn’t, how do they compare? And that’s very useful information.