Log: 4/30/2021

This week: prescribing math for gamblers, the hustle economy as a search function for capitalism, economic planning and control, beef and climate change, and the emerging phenomenon of acquisitions of Amazon sellers.

Mathematics for gamblers, Catalin Barboianu

I always like reading about randomness and probability because it’s so counterintuitive and uncertainty/risk management (more broadly, “security”) seems to be a decent explanation for so many behaviors. Gambling is one behavior that’s sometimes pathologized as a kind of innumeracy/ignorance about probability. If that’s the diagnosis, then people with gambling problems are told to “trust” the math…when gambling, like any social problem, isn’t just an issue of “irrationality” or ignorance but a complex interaction of personal history, biological/psychological factors, etc. The more interesting objection in the article is: what does it mean for someone to “trust” the math when applying mathematical knowledge is a skill in itself? You need to be able to evaluate what relationships are relevant to what situations, for example, and because probability is so counterintuitive, it’s very easy to misapply or misunderstand what you learn about it.

The Hustle Economy, Tressie McMillan Cottom

A great overview of the “hustle economy”, where “economic opportunity” as code for “opportunity to hustle” and is increasingly just “the economy” for many people. Existing hierarchies and oppressions are reproduced if not compounded within the hustle economy, e.g. through “subprime” services that provide financing at a higher cost to those who are ignored/excluded by existing entrepreneur infrastructure.

There is a weird romanticism around “the hustle” in a lot of media representations and I wonder how oppressive relationships come to be represented in that way (I’m kind of thinking of Nomadland right now).

In line with above, the hustle economy is risk shifting en masse; e.g. with Uber and other gig economy companies shifting as much risk as possible to their drivers/workers (I take it that the gig economy is a subset of the hustle economy).

One thing that’s been in my head wrt to the hustle economy is its “search” function for capitalism: if profits are harder to find, you need more people searching for opportunities for profit. With the hustle economy you have millions of people trying to find a big opportunity for themselves; if they hit upon success they often hit a wall in terms of scaling rapidly. Larger firms or more resourced entrepreneurs are able to swoop in, scale quickly, and push the original people out.

Planning and Anarchy, Jasper Bernes

Planning, or “economic calculation”, is a common point of disagreement on the left. “Planning” usually implies “central planning” and evokes a shadowy bureaucracy of distant politicians sending down quotas and reprimands, hoarding and number fudging among local officials or factories, and catastrophes of scarcity and ill-met needs: that is, complete dysfunction. The recent “algorithmization” of life has brought a renewed interest in the idea that perhaps instead of people, computers can do the planning (this is a fun read on how difficult this is in practice). There are varying degrees of this belief: that planning exclusively be left to a single or consortium of AIs à la Iain M. Banks’ Culture or that computers have some role to play in planning (seems reasonable). Though I’ve found the former more extreme position to be fairly common, at least as a desire if not a belief in something that will realistically happen soon, I’ve seen very little discussion on how that would come about or what that might look like (though there’s this article, The Problem of Scale in Anarchism and the Case for Cybernetic Communism, that goes into more technical details). I say this as someone who still views Cybersyn, a cybernetic planning system (incompletely) developed under Allende, as a valuable if flawed utopian project. This article by Jasper Bernes is probably the best thing I’ve read on this topic lately.

But planning is not just about knowing what resources you have and where (the measurement part of planning) and deciding how much to make of what and where and how those affect whatever it is you’re optimizing (the calculation part of planning)–it’s also about whether or not those plans can be executed. Bernes puts it well:

Beneath problems of calculation lay much deeper organizational issues. At stake in planning is not simply the question of whether or not all resources and all needs can be recorded and measured in terms of labor time or some other numeric marker, not simply the transparency of that data or its legibility in terms of a single measure. The more important question is about control—whether and how that measure can effect changes in the distribution of those resources in order to satisfy those evolving needs. Inasmuch as humans are involved, this is not only a technical problem to be solved by mathematical formula and computation algorithm but a political one to be solved by class struggle.

This really becomes a question of how you get people to follow the plan, and when states want people to behave a certain way they generally resort to violence:

inasmuch as people are involved in producing things, and inasmuch as those things have as their final end the satisfactions of the needs and desires of people, one cannot so easily separate the administration of things and the administration of people. The USSR had a broken system for administering people, and did so irrationally, relying on violence, and often gratuitous violence, to move the levers of a machinery inherited from capitalism.

This may not look all that different than the typical violence of life under capitalism: the commodification of needs, the linkage of waged labor and survival as a way to “incentivize” your participation as a worker.

Bernes also goes through the more fundamental challenges of planning:

there is a deeper epistemological problem here: preferences are not stable, nor are the types of things available to people. Once one leaves behind the assumption of a fixed and unchanging set of commodities organized by stable preferences then mathematical calculation confronts strong limits: one can’t really know what people may want in the future when one doesn’t know what will be available. For short-run calculation, one might mobilize the technologies of contemporary logistics, developing algorithmic systems that monitor inventories and stocks and make predictions about needed supply and future demand from such observations. But this would do little to guide decisions about long-term investments in plant and infrastructure, nor the allocation of labor, which can’t simply be whipped about from site to site, like a pallet of toilet paper. At some point, the planners themselves would have to choose between incompatible developmental paths based on only speculation about the future. Though they would be advised by referenda and juries, one might question whether a group of people should have such power in the first place.

Or that with central planning: “the planners would make themselves a target for capture by groups or factions wanting to gain privileged access to social wealth.”

“Planning” is of course not the same as “central planning”, and so these indictments are not against planning more generally. The possibility is left open of some kind of intensely local planning, for example, where it seems that at least some of these problems become more manageable. But it seems like some minimum scale is necessary to reliably fulfill all needs, and that local planning will eventually hit up against a more macro-level planning.

Beef Rules, Jonathan Foley

Beef consumption is a very hot topic wrt to climate change–massive pools of manure creating waste management and contamination problems, huge amounts of agricultural productivity diverted towards feed for livestock, flourishing conditions for disease and antibiotic resistance, methane emissions, not to mention horrendous conditions in CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations). As a solution you have people like Bill Gates advocating for synthetic and/or plant-based meat substitutes. These are problems of industrial beef production and not beef production in general. I’d read about cattle’s value in field preparation, e.g. consuming cover crop and incorporating it into the soil, so clearly there are alternatives. But it seems clear that current levels of beef consumption can’t be sustained in any other way (I’m not familiar enough with synthetic meat production to comment on that, only that in general we should be skeptical of these proposals). I left my understanding at that until I had more time to read about the topic.

I came across this piece and this Twitter thread by Paige Stanley on the topic via Max Ajl, which mostly confirmed my understanding. Grass-fed (grazing) beef can be beneficial in terms of climate change but can’t meet existing levels of consumption, though potentially up to 60% of it, possibly more with improved grazing techniques and with reduced wastage. Maybe the biggest challenge is that grass-fed beef requires more land, but as pointed out in the piece, this land might not have many competing uses (in terms of food production, at least).

The Great Amazon Flip-a-Thon, John Herrman

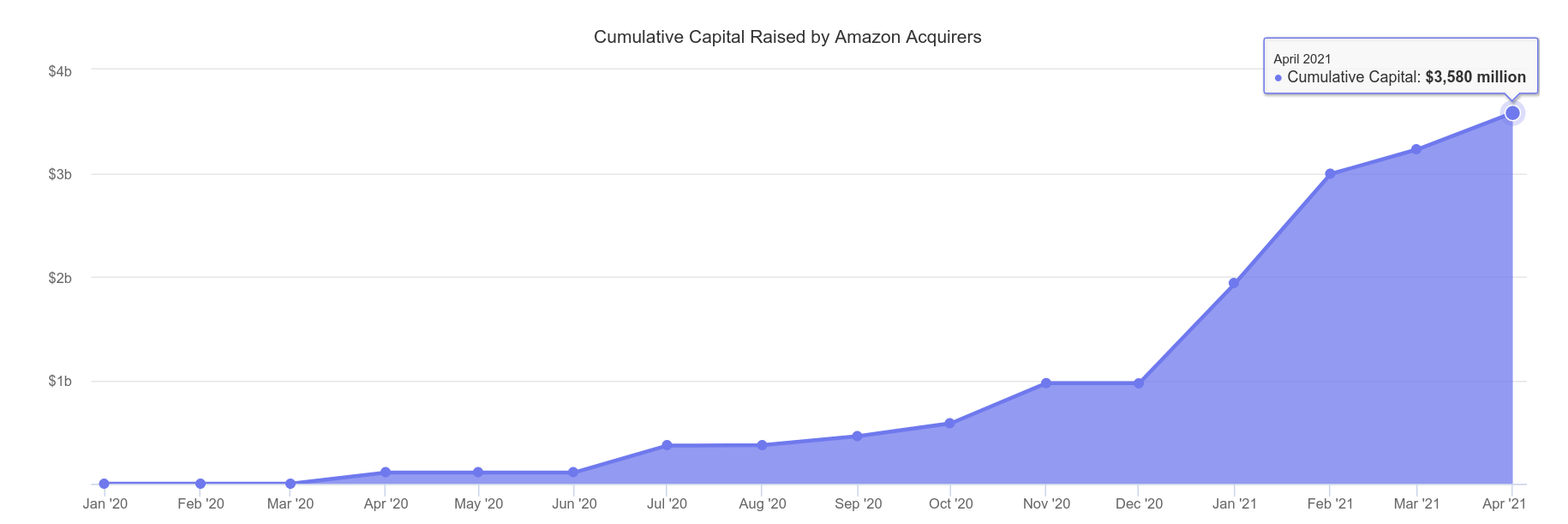

An emerging phenomenon in the Amazon ecosystem is the acquisition of sellers by investment firms. This isn’t something that I’d ever thought about but makes sense in retrospect–surprising to see, via the chart below, that this is really something that only took off over the past year. I wonder what impact it’ll have.

h/t Moira