Discovering high-quality comments and discussions

Say you have a lot of users commenting on your service, and inevitably all the pains of unfettered (pseudo-)anonymous chatter emerge - spam, abusive behavior, trolling, meme circlejerking, etc. How do you sort through all this cruft? You can get community feedback - up and down votes, for example - but then you have to make sense of all of that too.

There are many different approaches for doing so. Is any one the best? I don’t think so - it really depends on the particular context and the nuances of what you hope to achieve. There is probably not a single approach generalizable to all social contexts. We won’t unearth some grand theory of social physics which could support such a solution; things don’t work that way.

Nevertheless! I want to explore a few of those approaches and see if any come out more promising than the others. This post isn’t going to be exhaustive but is more of a starting point for ongoing research.

Goals

There are a lot of different goals a comment ranking system can be used for, such as:

- detection of spam

- detection of abusive behavior

- detection of high-quality contributions

Here, we want to detect high-quality contributions and minimize spam and abusive behavior. The three are interrelated, but the focus is detecting high-quality contributions, since we can assume that it encapsulates the former two.

Judge

First of all, what is a “good” comment? Who decides?

Naturally, it really depends on the site. If it’s some publication, such as the New York Times, which has in mind a particular kind of atmosphere they want to cultivate (top-down), that decision is theirs.

If, however, we have a more community-driven (bottom-up) site built on some agnostic framework (such as Reddit), then the criteria for “good” is set by the members of that community (ideally).

Size and demographics of the community also play a large part in determining this criteria. As one might expect, a massive site with millions of users has very different needs than a small forum with a handful of tight-knit members.

So what qualifies as good will vary from place to place. Imgur will value different kinds of contributions than the Washington Post. As John Suler, who originally wrote about the Online Disinhibition Effect, puts it:

According to the theory of “cultural relativity,” what is considered normal behavior in one culture may not be considered normal in another, and vice versa. A particular type of “deviance” that is despised in one chat community may be a central organizing theme in another.

To complicate matters further, one place may value many different kinds of content. What people are looking for varies day to day, so sometimes something silly is wanted, and sometimes something more cerebral is (BuzzFeed is good at appealing to both these impulses). But very broadly there are two categories of user contributions which may be favored by a particular site:

- low-investment: quicker to digest, shorter, easier to produce. Memes, jokes, puns, and their ilk usually fall under this category. Comments are are more likely made based on the headline rather than the content of the article itself.

- high-investment: lengthier, requires more thought to understand, and more work to produce.

For our purposes here, we want to rank comments according to the latter criteria - in general, comments tend towards the former, so creating a culture of that type of user contribution isn’t really difficult. It often happens on its own (the “Fluff Principle”[1]) and that’s what many services want to avoid! Consistently high-quality, high-investment user contribution is the holy grail.

I should also note that low-investment and high-investment user contributions are both equally capable of being abusive and offensive (e.g. a convoluted racist rant).

Comments vs discussions

I’ve been talking about high-quality comments but what we really want are high-quality discussions (threads). That’s the whole point of a commenting system, isn’t it? To get users engaged and discussing whatever the focus of the commenting is (an article, etc). So the relation of a comment to its subsequent or surrounding discussion will be an important criteria.

Our definition of high-quality

With all of this in mind, our definition of high-quality will be:

A user contribution is considered high quality if it is not abusive, is on-topic, and incites or contributes to civil, constructive discussion which integrates multiple perspectives.

Other considerations

Herd mentality & the snowball effect

We want to ensure that any comments which meet our criteria has equal opportunity of being seen. We don’t want a snowball effect[2] where the highest-ranked comment always has the highest visibility and thus continues to attract the most votes. Some kind of churn is necessary for keeping things fresh but also so that no single perspective dominates the discussion. We want to discourage herd mentality or other polarizing triggers [foo] [3].

Gaming the system

A major challenge in designing such a system is the preventing anyone from gaming the system. That is, we want to minimize the effects of Goodhart’s Law:

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

This includes automated attacks (e.g. bots promoting certain content) or corporate-orchestrated manipulation such as astroturfing (where a company tries to artificially generate a “grassroots” movement around a product or policy).

Minimal complexity

On the user end of things, we want to keep things relatively simple. We don’t want to have to implement complicated user feedback mechanisms for the sake of gathering more data solely for better ranking comments. We should leverage existing features of the comment (detailed below) where possible.

Distinguish comment ranking from ranking the user

Below I’ve included “user features” but we should take care that we judge the comment, not the person. Any evaluation system needs to recognize that some people have bad days, which doesn’t necessarily reflect on their general behavior[4]. And given enough signals that a particular behavior is not valued by the community, users can adjust their behavior accordingly - we want to keep that option open.

No concentration of influence

Expanding on this last point, we don’t want our ranking system to enable an oligarchy of powerusers, which has a tendency of happening in some online communities. This can draw arbitrary lines between users; we want to minimize social hierarchies which may work to inhibit discussion.

Transparency

Ideally whatever approach is adopted is intuitive enough that any user of the platform can easily understand how their submissions are evaluated. Obscurity is too often used as a tool of control.

Adaptable and flexible

Finally, we should be conscious of historical hubris and recognize that it’s unlikely we will “get it right” because getting it right is dependent on a particular cultural and historical context which will shift and evolve as the community itself changes. So whatever solution we implement, it should be flexible.

Our goals

In summary, what we hope to accomplish here is the development of some computational approach which:

- requires minimal user input

- requires minimal user input

- minimizes snowballing/herd mentality effects

- is difficult to game by bots, astroturfers, or other malicious users

- promotes high-quality comments and discussions (per our definition)

- penalizes spam

- penalizes abusive and toxic behavior

- is easy to explain and intuitive

- maintains equal opportunity amongst all commenters (minimizes poweruser bias)

- adaptable to change in community values

What we’re working with

Depending on how your commenting system is structured, you may have the following data to work with:

- Comment features:

- noisy user sentiment (simple up/down voting)

- clear user sentiment (e.g. Slashdot’s more explicit voting: “insightful”, for instance.)

- comment length

- comment content (the actual words that make up the comment)

- posting time

- the number of edits

- time interval between votes

- Thread features:

- length of the thread’s branches (and also the longest, min, avg, etc branch length)

- number of branches in the thread

- Moderation activity (previous bans, deletions, etc)

- Total number of replies

- Length of time between posts

- Average length of comments in the thread

- User features:

- aggregate historical data of this user’s past activity

- some value of reputation

Pretty much any commenting system includes a feature where users can express their sentiment about a particular comment. Some are really simple (and noisy) - basic up/down voting, for instance. It’s really hard to tell what exactly a user means by an up or a downvote - myriad possible reactions as reduced to a single surface form. Furthermore, the low cost of submitting a vote means they will be used more liberally, which is perhaps the intended effect. But introducing high-cost unary or binary voting systems, such as Reddit Gold (which requires purchase before usage), have a scarcity which is a bit clearer in communicating the severity of the feedback. The advantage of low-cost voting is that its more democratic - anyone can do it. High-cost voting introduces barriers which may bar certain users from participating.

Other feedback mechanisms are more sophisticated and more explicit about the particular sentiment the user means to communicate. Slashdot allows randomly-selected moderators to specify whether a comment was insightful, funny, flamebait, etc, where each option has a different voting value.

I’ve included user features here, but as mentioned before, we want to rate the comment and discussion while trying to be agnostic about the user. So while you could have a reputation system of some kind, it’s better to see how far you can go without one. Any user is wholly capable of producing good and bad content, and we care only about judging the content.

Approaches

Caveat: the algorithms presented here are just sketches meant to convey the general idea behind an approach.

Basic vote interpretation

The simplest approach is to just manipulate the explicit user feedback for a comment:

score = upvotes - downvotes

But this approach has a few issues:

- scores are biased towards post time. The earlier someone posts, the greater visibility they have, therefore the greater potential they have for attracting votes. These posts stay at the top, thus maintaining their greater visibility and securing that position (snowballing effect).

- it may lead to domination and reinforcement of the most popular opinion, drowning out any alternative perspectives.

In general, simple interpretations of votes don’t really provide an accurate picture.

A simple improvement here would be to take into account post time. We can penalize older posts a bit to try and compensate for this effect.

score = (upvotes - downvotes) - age_of_post

Reddit used this kind of approach but ended up biasing post time too much, such those who commented earlier typically dominated the comments section. Or you could imagine someone who posts at odd hours - by the time others are awake to vote on it, the comment is already buried because of the time penalty.

This approach was later replaced by a more sophisticated interpretation of votes, taking them as a statistical sample rather than a literal value and using that to estimate a more accurate ranking of the comment (this is Reddit’s “best” sorting):

If everyone got a chance to see a comment and vote on [a comment], it would get some proportion of upvotes to downvotes. This algorithm treats the vote count as a statistical sampling of a hypothetical full vote by everyone, much as in an opinion poll. It uses this to calculate the 95% confidence score for the comment. That is, it gives the comment a provisional ranking that it is 95% sure it will get to. The more votes, the closer the 95% confidence score gets to the actual score.

If a comment has one upvote and zero downvotes, it has a 100% upvote rate, but since there’s not very much data, the system will keep it near the bottom. But if it has 10 upvotes and only 1 downvote, the system might have enough confidence to place it above something with 40 upvotes and 20 downvotes – figuring that by the time it’s also gotten 40 upvotes, it’s almost certain it will have fewer than 20 downvotes. And the best part is that if it’s wrong (which it is 5% of the time), it will quickly get more data, since the comment with less data is near the top – and when it gets that data, it will quickly correct the comment’s position. The bottom line is that this system means good comments will jump quickly to the top and stay there, and bad comments will hover near the bottom.

Here is a pure Python implementation, courtesy of Amir Salihefendic:

from math import sqrt def _confidence(ups, downs): n = ups + downs if n == 0: return 0 z = 1.0 #1.0 = 85%, 1.6 = 95% phat = float(ups) / n return sqrt(phat+z*z/(2*n)-z*((phat*(1-phat)+z*z/(4*n))/n))/(1+z*z/n) def confidence(ups, downs): if ups + downs == 0: return 0 else: return _confidence(ups, downs)

Reddit’s Pyrex implementation is available here.

The benefit here is you no longer need to take post time into account. When you are getting the vote count doesn’t matter, all that matters is the sample size!

Manipulating the value of votes

How you interpret votes depends on how you collect and value you them. Different interaction design of voting systems, even if the end result is just up or downvote, can influence the value users place on a vote and under what conditions they submit one.

For instance, Quora makes only upvoters visible and hides downvoters. This is a big tangent so I will just leave it at that for now.

In terms of valuing votes, it’s been suggested that a votes should not be equal - that they should be weighted according to the reputation of the voter:

- Voting influence is not the same for all users: its not 1 (+1 or -1) for everyone but in the range 0-1.

- When a user votes for a content item, they also vote for the creator (or submitter) of the content.

- The voting influence of a user is calculated using the positive and negative votes that he has received for his submissions.

- Exemplary users always have a static maximum influence.

Although like any system where power begets power, there’s potential for a positive feedback loop where highly-voted people amass all the voting power and then you have an poweruser oligarchy.

Using features of the comment

For instance, we could use the simple heuristic: longer comments are better.

Depending on the site, there is some correlation between comment length and comment quality. This appears to be the case with Metafilter and Reddit:

(or at least we can say more discussion-driven subreddits have longer comments).

Using the structure of the thread.

Features of the thread itself can provide a lot of useful information.

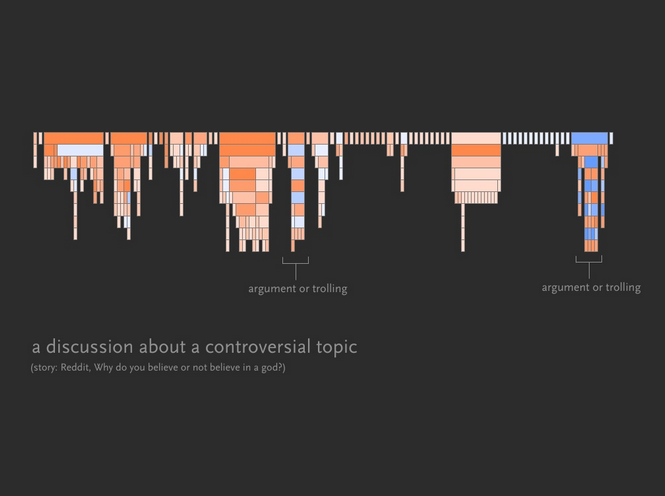

Srikanth Narayan’s tldr project visualizes some heuristics we can use for identifying certain types of threads.

A few examples from that project:

Conclusion

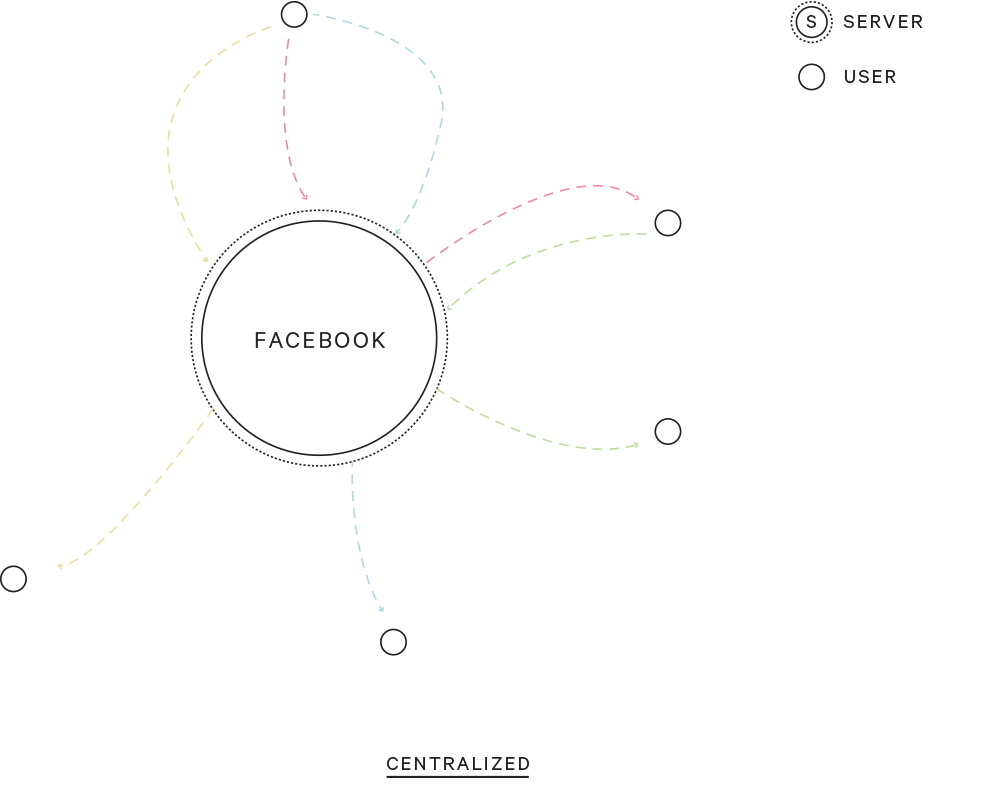

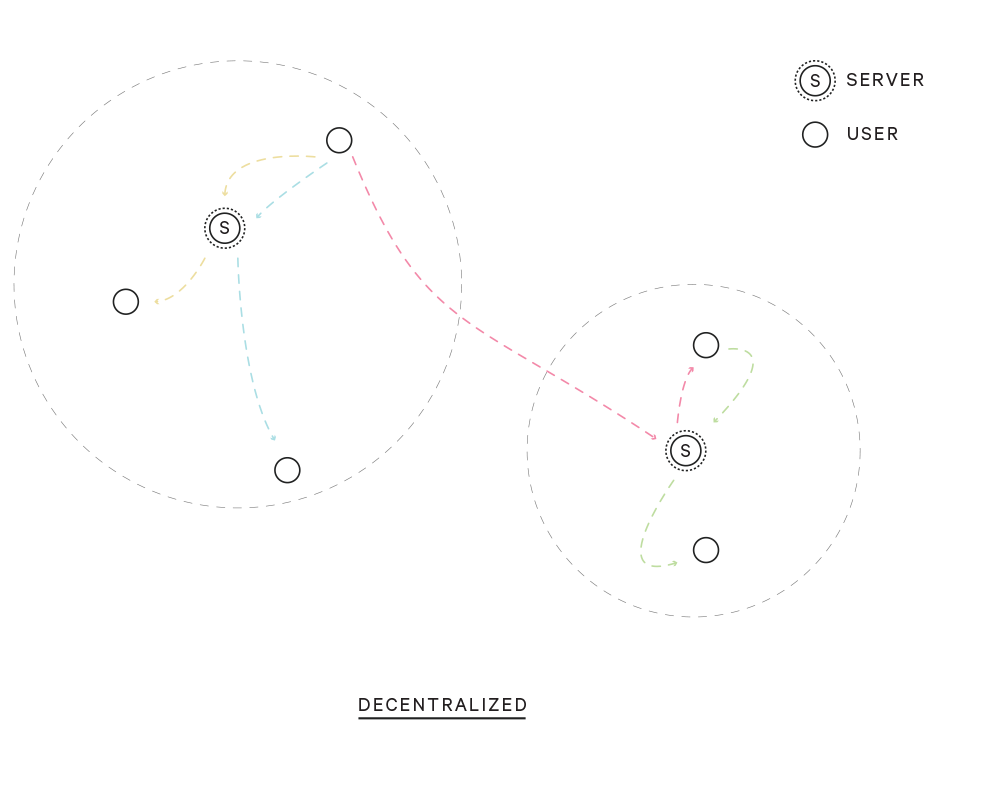

Here I’ve only discussed a few approaches for evaluating the quality of comments and using that information to rank and sort them. But there are other techniques which can be used in support of the goals set out at the start of this post. For example, posting frequency or time interval limits could be set to discourage rapid (knee-jerk?) commenting, or the usage of real identities could be made mandatory (ala Facebook, not a very palpable solution), or scale posting privileges (ala Stack Overflow) or limit them to only certain users (ala Metafilter). Gawker’s Kinja allows the thread parent to “dismiss” any child comments. You could provide explicit structure for responses, as the New York Times has experimented with. Disqus creates a global reputation across all its sites, but preserves some frontend pseudonymity (you can appear with different identities, but the backend ties them all together).

Spamming is best handled by shadowbanning, where users don’t know that they’re banned and have the impression that they are interacting with the site normally. Vote fuzzing is a technique used by Reddit where actual vote counts are obscured so that voting bots have difficulty verifying their votes or whether or not they have been shadowbanned.

What I’ve discussed here are technical approaches, which alone cannot solve many of the issues which plague online communities. The hard task of changing peoples’ attitudes is pretty crucial too.

As Joshua Topolsky of the Verge ponders:

Maybe the way to encourage intelligent, engaging and important conversation is as simple as creating a world where we actually value the things that make intelligent, engaging and important conversation. You know, such as education, manners and an appreciation for empathy. Things we used to value that seem to be in increasingly short supply.

[1]: The Fluff Principle, as described by Paul Graham:

on a user-voted news site, the links that are easiest to judge will take over unless you take specific measures to prevent it. (source)

User LinuxFreeOrDie also runs through a theory on how user content sites tend towards low-investment content. The gist is that low-investment material is quicker to digest and more accessible, thus more people will vote on it more quickly, so in terms of sheer volume, that content is most likely to get the highest votes. A positive feedback effect happens where the low-investment material subsequently becomes the most visible, therefore attracting an even greater share of votes.

[2]: Users are pretty strongly influenced by the existing judgement on a comment, which can lead to a snowballing effect (at least in the positive direction.):

At least when it comes to comments on news sites, the crowd is more herdlike than wise. Comments that received fake positive votes from the researchers were 32% more likely to receive more positive votes compared with a control…And those comments were no more likely than the control to be down-voted by the next viewer to see them. By the end of the study, positively manipulated comments got an overall boost of about 25%. However, the same did not hold true for negative manipulation. The ratings of comments that got a fake down vote were usually negated by an up vote by the next user to see them. (source)

[3]: Researchers at George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication found that negative comments set the tone for a discussion:

The researchers were trying to find out what effect exposure to such rudeness had on public perceptions of nanotech risks. They found that it wasn’t a good one. Rather, it polarized the audience: Those who already thought nanorisks were low tended to become more sure of themselves when exposed to name-calling, while those who thought nanorisks are high were more likely to move in their own favored direction. In other words, it appeared that pushing people’s emotional buttons, through derogatory comments, made them double down on their preexisting beliefs. (source)

[4]: Riot Games’s player behavior team found that toxic behavior is typically sporadically distributed amongst normally well-behaving users:

if you think most online abuse is hurled by a small group of maladapted trolls, you’re wrong. Riot found that persistently negative players were only responsible for roughly 13 percent of the game’s bad behavior. The other 87 percent was coming from players whose presence, most of the time, seemed to be generally inoffensive or even positive. These gamers were lashing out only occasionally, in isolated incidents–but their outbursts often snowballed through the community. (source)